PodcastsText

HighlightsThe Hope in Every Jew - Perek 14

Yirmiyahu describes a terrible future coming. There is irreversible destruction on the way because Israel ignored the red flags. But as the destruction approaches, Yirmiyahu turns from being the plaintiff of Israel to their defender in front of Hashem. He begs the Almighty for mercy and points to their virtue. In one argument, Yirmiyahu says the following.

Yirmiyahu 14:8

מִקְוֵה, יִשְׂרָאֵל, מוֹשִׁיעוֹ, בְּעֵת צָרָה--לָמָּה תִהְיֶה כְּגֵר בָּאָרֶץ, וּכְאֹרֵחַ נָטָה לָלוּן

O Hope of Israel, Its deliverer in time of trouble, Why are You like a stranger in the land, Like a traveler who stops only for the night?

The Radak explains that even when Jews stray far, far away from Hashem, still deep down, they hope to and depend on Hashem as their support and savior. This deep-seated hope expresses itself in some moving moments in Jewish history.

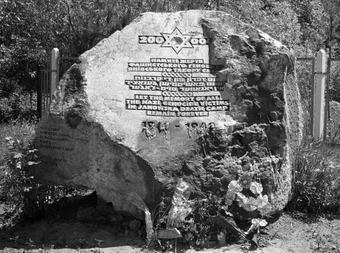

Here is a story recorded by Yaffa Eliach in her work Chasidic Tales of the Holocaust, Vintage Books, 1988, pp. 155-159. In the Janowska Road Camp, there was a foreman of a brigade from Lvov by the name of Schneeweiss, one of those people one stays away from if he values life. He had known Rabbi Israel Spira in Lemberg (Lvov), but was not aware that the latter was an inmate in the camp. Only a handful of Chasidim who were close to the rabbi knew the rabbi’s identity and they kept it a secret. The season of the Jewish holidays was approaching. As the date of Yom Kippur was nearing, the fears in the camp mounted. Everyone knew that the Germans especially liked to use the Jewish holidays as days for inflicting terror and death. In Janowska, a handful of old-timers remembered large selections on Simchat Torah and Purim. It was the eve of Yom Kippur. The tensions and fears were at their height. A few Chasidim came to the Rabbi of Bluzhov and asked him to approach Schneeweiss and request that on Yom Kippur his group not be assigned to any of the thirty-nine main categories of work, so that their transgression of the law by working on Yom Kippur would not be a major one. The rabbi was very moved by the request, and despite his fears, for he would have to disclose his identity, went to Schneeweiss. He knew quite well that Schneeweiss did not have much respect for Jewish tradition. Even prior to the outbreak of World War II, he had publicly violated the Jewish holidays and transgressed Jewish law. Here in Janowska, he was a cruel man who knew no mercy. With a heavy heart the rabbi went before Schneeweiss. “You probably remember me. I am the rabbi of Pruchnik, Rabbi Israel Spira.” Schneeweiss did not respond. “You are a Jew like myself,” the rabbi continued. “Tonight is Kol Nidrei night. There is a small group of young Jews who do not want to transgress any of the thirty-nine main categories of work. It means everything to them. It is the essence of their existence. Can you do something about it? Can you help?” The rabbi noticed that a hidden shiver went through Schneeweiss as he listened to the rabbi’s strange request. The rabbi took Schneeweiss’s hand and said, “I promise you, as long as you live, it will be a good life. I beg you to do it for us so that we may still find some dignity in our humiliating existence.” The stern face of Schneeweiss changed. For the first time since his arrival in Janowska, there was a human spark in it. “Tonight I can’t do a thing,” said Schneeweiss, the first words he had uttered since the rabbi had come to him. “I have no jurisdiction over the night brigade. But tomorrow, on Yom Kippur, I will do for you what I can.” The rabbi shook Schneeweiss’s hand in gratitude and left. In the morning, the rabbi and small group of young Chasidim were summoned to Schneeweiss’s cottage. “I heard that you prayed last night. I don’t believe in prayers,” Schneeweiss told them. “On principle, I even oppose them. But I admire your courage. For you know well that the penalty for prayer in Janowska is death.” With that he motioned them to follow him. He took them to the S.S. headquarters in the camp, to a large wooden house. “You fellows will shine the floor without any polish or wax. And you, rabbi, will clean the window with dry rags so that you will not transgress any of the thirty-nine categories of work.” He left the room abruptly without saying another word. At about twelve o’clock noon, the door opened wide and into the room stormed two angels of death, S.S. men in their black uniforms, may their names be obliterated. They were followed by a food cart filled to capacity. “Noontime, time to eat bread, soup, meat,” announced one of the S.S. men. The room was filled with an aroma of freshly cooked food, such food as they had not seen since the German occupation: white bread, steaming hot vegetable soup, and huge portions of meat. The tall S.S. man commanded in a high-pitched voice, “You must eat immediately, otherwise you will be shot on the spot!” None of them moved. The rabbi remained on the ladder, the Chasidim on the floor. The Germans repeated the orders. The rabbi and the Chasidim remained glued to their places. The S.S. man called to Schneeweiss. “Schneeweiss, if the dirty dogs refuse to eat, I will kill you along with them.” Schneeweiss pulled himself to attention, looked the German directly in the eyes, and said in a very quiet tone, “We Jews do not eat today. Today is Yom Kippur, our most holy day, the Day of Atonement.” “You don’t understand, Jewish dog,” roared the taller of the two. “I command you in the name of the Fuhrer and the Third Reich, fress!” Schneeweiss, composed, his head high, repeated the same answer. “We Jews obey the law of our tradition. Today is Yom Kippur, a day of fasting.” The German took out his revolver from its holster and pointed it at Schneeweiss’s temple. Schneeweiss remained calm. He stood still, at attention, his head high. A shot pierced the room. Schneeweiss fell. On the freshly polished floor, a puddle of blood was growing bigger and bigger. The rabbi and the Chasidim stood as if frozen in their places. They could not believe what their eyes had just witnessed. Schneeweiss, the man who in the past had publicly transgressed against the Jewish tradition, had sanctified God’s Name publicly and died a martyr’s death for the sake of Jewish honor. (Yaffa Eliach, Chasidic Tales of the Holocaust, Vintage Books, 1988, pp. 155-159, excerpt based on a conversation with the Grand Rabbi of Bluzhov, Rabbi Israel Spira.) Comments

0 Comments

PodcastsText

HighlightsMissing the Bracha - Yirmiyahu 9

In Perek 9, Yirmiyahu asks the heavy question. Why did all this happen? Why did all this terrible destruction befall the land and the people of Israel? The pesukim themselves are pretty obscure. H' seems to respond that it is because they abandoned the Torah.

The Talmud Bavli, Nedarim 81a, gives us a little of the subtext to this conversation.

דאמר רב יהודה אמר רב מאי דכתיב (ירמיהו ט, יא) מי האיש החכם ויבן את זאת דבר זה נשאל לחכמים ולנביאים ולא פירשוהו עד שפירשו הקב"ה בעצמו דכתיב (ירמיהו ט, יב) ויאמר ה' על עזבם את תורתי וגו' היינו לא שמעו בקולי היינו לא הלכו בה אמר רב יהודה אמר רב שאין מברכין בתורה תחלה

As Rav Yehuda said that Rav said: What is the meaning of that which is written: “Who is the wise man that may understand this, and who is he to whom the mouth of the Lord has spoken, that he may declare it, for what the land is perished and laid waste like a wilderness, so that none passes through” (Jeremiah 9:11)? This matter, the question as to why Eretz Yisrael was destroyed, was asked of the Sages, i.e., “the wise man,” and of the prophets, “he to whom the mouth of the Lord has spoken,” but they could not explain it.

The matter remained a mystery until the Holy One, Blessed be He, Himself explained why Eretz Yisrael was laid waste, as it is written in the next verse: “And the Lord said: Because they have forsaken My Torah which I set before them, and have not obeyed My voice, nor walked therein” (Jeremiah 9:12). It would appear that“have not obeyed My voice” is the same as “nor walked therein.” Rav Yehuda said that Rav said: The expression “nor walked therein” means that they do not first recite a blessing over the Torah, and they are therefore liable to receive the severe punishments listed in the verse. This Gemara just complicates things, doesn't it? Instead of explaining what the sin was, it seems to identify a trivial factor - the lack of blessing on the Torah which was the cause of of the evil. Really? They left out one bracha and for that, the land was destroyed?! Rabbeinu Nissim, in his commentary on this Gemara interjects a beautiful explanation from Rabbeinu Yonah of Gerona. He points out that the reason that no other entity in the world could answer this question was because outwardly the people were studying Torah. They were keeping Mitzvos. The seemed to lead exemplary lives. It was only the Almighty Himself who could see there was no heart in it. The performed their rituals as insurance policies to protect themselves. They weren't really into it. The indicator that something was off, was the fact that although they learned Torah and they performed Torah, they didn't bless the Torah they learned. It didn't mean so much in their lives. In Rabbeinu Nissim's own words.

עד שפרשו הקב''ה בעצמו שהוא יודע מעמקי הלב שלא היו מברכין בתורה תחלה כלומר שלא היתה התורה חשובה בעיניהם כ''כ שיהא ראוי לברך עליה שלא היו עוסקים בה לשמה ומתוך כך היו מזלזלין בברכתה והיינו לא הלכו בה כלומר בכונתה ולשמה

CommentsPodcastsText

HighlightsHearts not Sacrifices

In perek 7, Yirmiyahu talks to a people who has been in the throes of spiritual revolution in the days of Yoshiyahu. Yirmiyahu sees through the thin veneer and realizes that the commitment is not real. He criticizes them for them empty sacrifices.

Yirmiyahu 7:22-23

ז,כב כִּי לֹא-דִבַּרְתִּי אֶת-אֲבוֹתֵיכֶם, וְלֹא צִוִּיתִים, בְּיוֹם הוציא (הוֹצִיאִי) אוֹתָם, מֵאֶרֶץ מִצְרָיִם--עַל-דִּבְרֵי עוֹלָה, וָזָבַח. ז,כג כִּי אִם-אֶת-הַדָּבָר הַזֶּה צִוִּיתִי אוֹתָם לֵאמֹר, שִׁמְעוּ בְקוֹלִי--וְהָיִיתִי לָכֶם לֵאלקים, וְאַתֶּם תִּהְיוּ-לִי לְעָם; וַהֲלַכְתֶּם, בְּכָל-הַדֶּרֶךְ אֲשֶׁר אֲצַוֶּה אֶתְכֶם, לְמַעַן, יִיטַב לָכֶם

For when I freed your fathers from the land of Egypt, I did not speak with them or command them concerning burnt offerings or sacrifice.

But this is what I commanded them: Do My bidding, that I may be your God and you may be My people; walk only in the way that I enjoin upon you, that it may go well with you. CommentsPodcastsText

HighlightsMakel Shaked

Comments |

Nach YomiHere's the way it works. From Monday to Thursday I will be posting a 5 minute podcast of the chapter of the day. It will be a brief summary with a few points to ponder. I will also be sending out the Sefaria text so you can use it. Archives |

Proudly powered by Weebly